|

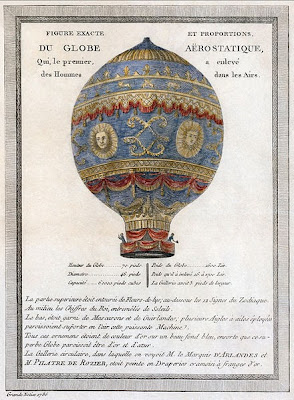

| Nicolas-Henri Jardin by Peder Als, 1764 |

Much as I adore my tottering abode on Henrietta Street, there's no denying that it can be a little bit higgledy piggledy. Our subject today is a man who never went near tottering and to whom higgledy piggledy would have been blasphemy; in fact, he was one of the giants of neoclassical architecture and like so many of our recent guests, he hailed from France.

Nicolas-Henri Jardin was barely into double figures when he took up a serious interest in architecture and by the age of 18 was enrolled at the Académie Francaise. A diligent and exemplary student, Jardin became a star student and in 1744 designed a cathedral chancel that won him the Prix de Rome for architecture. With the money he received from the prize he followed so many other artists and creatives to Italy and a place at the prestigious Académie Francaise in Rome, where he would remain until 1748. Here he befriended sculptor Jacques François Joseph Saly and the two would be lifelong friends, with Saly eventually providing Jardin with his greatest opportunities.

|

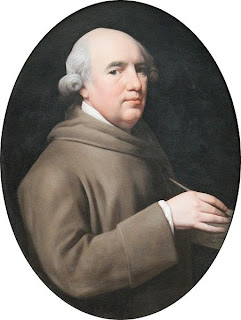

| Marienlyst Castle, Helsingør |

Their studies and roaming concluded, Saly travelled to Denmark to work at the court of King Frederik V whilst Jardin returned to Paris where he would take up the position of resident architect with Michel Tannevot in 1753. In fact, Jardin only remained in Tannevot's employ for a year as the winds of change were blowing through the Danish court. With something of an overhaul of personnel taking place, there was a need for an innovative, talented architect to complete Frederikskirken, a project begun by Nicolai Eigtved five years earlier, before the architect fell from favour with Frederik.

Saly suggested that his travelling companion from Italy might fit the bill and by the end of 1754, Jardin was in Copenhagen with his apprentice brother, Louis Henri. With a year they were members of Royal Danish Academy of Art, lecturing on architecture under the Director, who just happened to be Jardin's old friend, Saly.

|

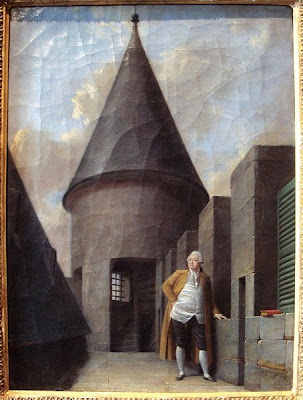

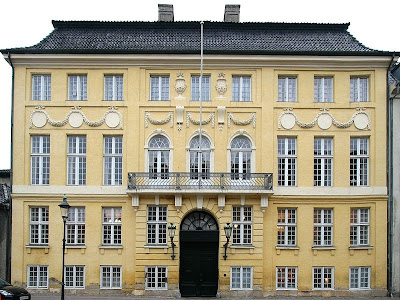

| The Yellow Palace, Copenhagen |

When Jardin presented the plans for the church to the Royal Building Commission, they were horrified at the enormous expense of the project; not to be deterred, he made minor amendments and resubmitted his work. Once again the Commission balked at the cost yet this time Jardin had already secured the agreement of the King, who declared that work would begin immediately. Due to the complexity of the plans the building process was painfully slow and funds were not always quick to materialise yet Jardin maintained his position of favour at court, taking the role of Royal Building Master in 1760.

Throughout his career, Jardin received many prestigious decorations and plaudits but the stability that he enjoyed as a courtier of Frederik was threatened by the death of the old king and the succession of his unstable son, Christian VII. In 1770 it was projected that the church would not be fully completed for almost eighty years and Christian's advisor, Johann Friedrich Struensee, advised that building should stop for a time in order for the country to divert some of the money that was being ploughed into the project. Jardin was paid off and the unfinished church was left to the elements, falling into ruin before construction finally resumed in 1874.

|

| Bernstorff Palace, Copenhagen |

|

| Frederik's Church, Copenhagen |

Amazon UK

Amazon US

Book Depository (free worldwide shipping)