It is a pleasure to welcome back the fabulous Jacqui Reiter with the heartbreaking tale of Mary, Countess of Chatham.

---oOo---

|

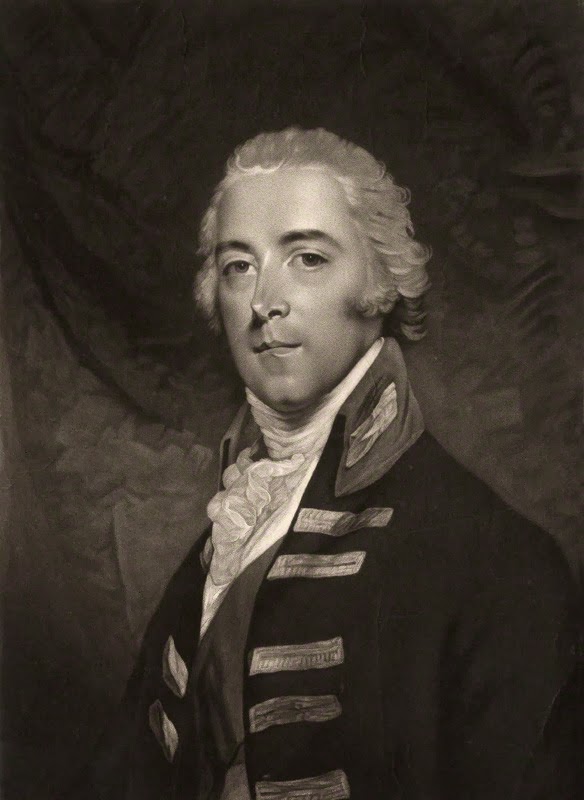

| Mary Elizabeth, Countess of Chatham |

I would like to introduce you to the beautiful, tragic and virtually unknown Mary, Countess of Chatham, who died 193 years ago today. She was the sister-in-law of prime minister William Pitt the Younger and confidante of several royal princesses, yet teasing her life out of the historical record is not easy. She was a shy and deeply private person who lacked the ambitious thrust that made a good political hostess; she also suffered most of her life from chronic ill-health. The more I've found out about her, however, the more I like her, and studying her life has provided its fair share of surprises.

She was born Mary Elizabeth Townshend on 2 September 1762, the second child of Thomas Townshend, later Lord Sydney. She and her six surviving siblings grew up at Frognall, near Chislehurst, Kent. Townshend's political patron was William Pitt the Elder, Earl of Chatham, whose country residence at Hayes was only a few miles from Frognall. The Townshend children were only a little younger than the Pitt children and the two families saw a great deal of each other.[1]

|

| Frognall, Chislehurst, Kent |

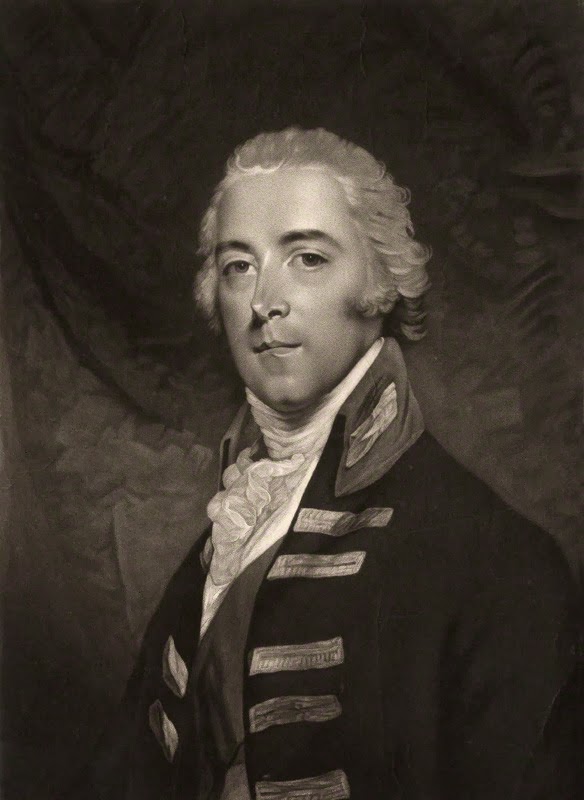

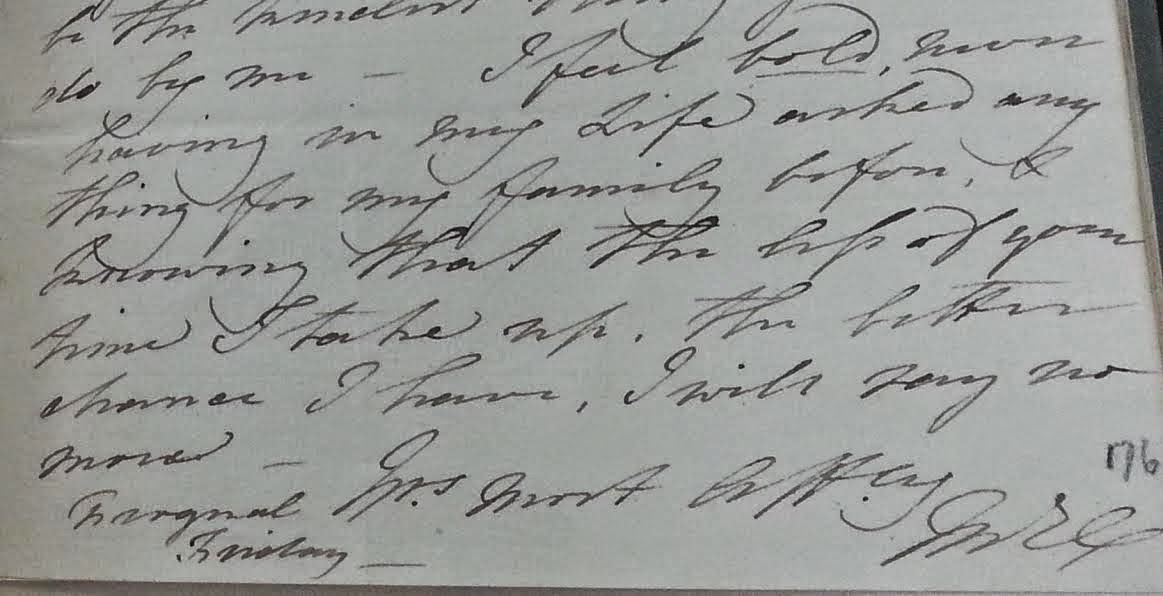

By the summer of 1782 Mary had attracted the attention of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham. He was six years Mary's senior and had just come back from military service in the West Indies. It was a love match between childhood sweethearts and when John proposed on 5 June 1783 Lord Sydney was delighted: “We feel at present the full Value of the Vicinity of Hayes & Frognall, which I have indeed long been used to look upon as one of the most fortunate Circumstances of my Life”.[2] The wedding took place on 10 July 1783 at the Sydneys' house on Albemarle Street. Mary brought a dowry of £2000 and £3000 worth of West India stock.[3] The couple settled into Lord Chatham's new house on Berkeley Square, where they were joined by Chatham's brother William.

|

| John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham by Valentine Green, after John Hoppner mezzotint, 1799 |

The household was almost immediately plunged into the events surrounding Pitt the Younger's rise to power as prime minister. The house was a major political hub from November 1783 until Pitt moved into 10 Downing Street in April 1784. It should have been an excellent opportunity for the new Countess of Chatham to become the government's hostess, but that role fell to the Duchess of Rutland and Lady Salisbury. Mary's character was not suited to political sparring, and in any case by early 1784 she was severely unwell.

Throughout her life Mary suffered from a mysterious “rheumatic” complaint. In April 1784—at the height of the general election that confirmed Pitt in power—Mary was at her worst. “It is really quite horrid to think how much she has suffered,” Mary's sister Georgiana wrote to the Dowager Countess of Chatham: “... what would I give to see her walk again!”[4] She was not totally well until the end of the year, and relapsed in the summer of 1785.[5] The illness left her permanently lame and drove her to seek help from the fashionable surgeon Miles Partington. His “electrical therapy” sounds highly unpleasant, but Mary found “great benefit from being Electrified” and continued with the therapy as late as 1796.[6] Mary's condition, whatever it was, may have been exacerbated by miscarriages. She never carried a child to term but she was certainly pregnant at least once, in November 1786.[7]

Despite this ill health Mary did have a public role. When her husband was made First Lord of the Admiralty in 1788 she took on the duties of a cabinet member's wife. She was active in the 1788 by-election at Westminster in which the Pittite Lord Hood challenged the Foxite Lord John Townshend for the constituency's second seat. Mary and her sister were out canvassing every day. “We were very successful indeed yesterday, & I hope shall be so today,” Georgiana reported, but Hood eventually lost the election.[8]

|

| Mary's signature on her marriage settlement, July 1783 |

The following year Mary joined the Duchesses of Gordon and Rutland as a Patroness of White's Club's ball at the Pantheon to celebrate the King's recovery from insanity.[9] She showed her ability to keep calm under pressure when she more or less single-handedly organised an unexpected visit by the Royal Family to Greenwich in February 1793, coolly making arrangements for feeding and accommodating the King and Queen for the visit.[10] It was Mary who first publicly announced news of the naval victory of the Glorious First of June at the Opera in 1794; and when her husband returned to his military career, she followed him to all his home-based postings and entertained the Royal Family during several military reviews.[11] She was an object of admiration at Court whenever she appeared: “LADY CHATHAM was very elegantly dressed in white, embroidered with spangles, with two long wreaths of laural leaves across the petticoat”; “LADY CHATHAM: a very rich dress. The body and train white sattin; petticoat the same, covered with crape, superbly embroidered with stones, purple and green foil, and gold spangles”; “white satin petticoat elegantly embroidered with gold vermicelli … the most superb border of purple velvet, beautifully spangled … with rich embroidered tassels”.[12]

Even so, Mary rarely pushed herself forwards. She was neither robust nor adventurous, and she did not wish to be involved in politics: “The Cabinet dine here, and I must get out of their way”.[13] It was evidently her wish to stay in the background as much as possible:

“She from the yielding of her gentle heart,

Still walked fair honor's handmaid, early spurned

The flaunting scenes of Court parade, to act

The humble duties of Domestic life...”[14]

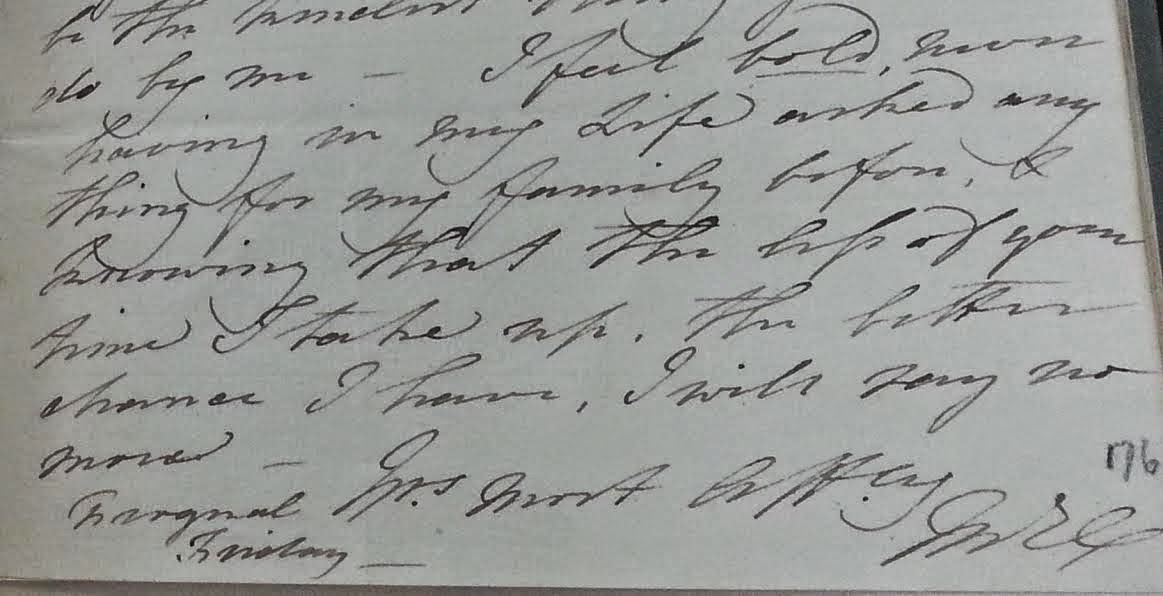

Very few letters of Mary's survive: none to her husband, and only a handful to her brother-in-law, all about patronage and layered in apologies: “Adieu, my dear Mr Pitt, forgive my plaguing you, & believe me, Yours most affectionately ME Chatham”.[15] Some thought Mary and Pitt did not get on, but I'm not convinced.[16] When Pitt died in January 1806 Mary's devastation was so great she had a nervous breakdown. “Lady Chatham is seriously ill,” the Bishop of Lincoln wrote. “She has fretted herself with a delirious Fever”.[17] She was so ill Chatham doubted he could attend his brother's funeral, but she recovered enough by the middle of February to allow him to go.[18]

|

| Letter from Mary to Pitt, PRO 30/08/122 f 174 |

Alas it was only the first of several bouts of depression. In 1807 she had a lengthy collapse. She put a brave face on for the world, drugging herself up to attend assemblies and Court drawing-rooms, but she was unable to keep her condition secret. This was around the time that Lord Chatham was being considered as a replacement for the ailing First Lord of the Treasury, the Duke of Portland, and Mary's illness encouraged him to decline: “Lady Chatham is much disordered in her senses, and that circumstance is said to have confirmed Lord Chatham in his determination not to succeed to the Duke of Portland”.[19] Mary's illness may also help explain why Chatham did not serve in the Peninsula.

Mary recovered enough for her husband to agree (disastrously) to command the failed expedition to Walcheren in 1809. She followed Chatham into retirement and, for a while, they seem to have enjoyed being out of the public eye. In March 1818, however, Mary had a serious relapse. In February 1819 her distraught husband managed to persuade her to stay with her brother and sister at Frognall, but the change of scene did not help and by September she was hysterical, self-harming and suicidal.[20] Her physician Sir Henry Halford suggested straitjacketing, which Chatham flatly refused to do. Nothing helped and Mary drifted in and out of depression for the next year.[21]

She recovered enough in 1821 for her husband to announce his determination to take up his post as Governor of Gibraltar, which he had held since January 1820, and for Mary to re-emerge into society.[22] On 12 May she was recorded as one of the patronesses of a ball to be held on the 28th.[23] On the 21st, however, at five o'clock in the evening, Mary died at Lord Chatham's house in Hill Street, London, aged only fifty-eight. The Morning Post described her death as “very sudden”, yet every newspaper that ran her obituary stated Mary “had been indisposed nearly two years”.[24]

![[Image 6: 38 Hill Street, now the Naval Club, where Mary died: photograph by Stephenie Woolterton]](https://1.bp.blogspot.com/-rmRS6eT7Jh4/U3Y-33sLQGI/AAAAAAAAC0Q/r7oaFVJCrYI/s1600/unnamed.jpg) |

| Image 6: 38 Hill Street, now the Naval Club, where Mary died: photograph by Stephenie Woolterton |

Given her age and the nature of her “indisposition”, not to mention the fact that her death seems to have been unexpected, I cannot help wondering if it was self-inflicted. Perhaps the prospect of Chatham's departure for Gibraltar helped push her over the edge. Of course it is possible her death was entirely natural: she had, after all, never been physically strong.

She was buried on 30 May 1821 in the Pitt family vault at Westminster Abbey. “Her body was deposited in great state,” the Gentleman's Magazine recorded, “... and was followed by 50 carriages of the Nobility, &c”.[25] It was a tragic ending for the young girl who first appeared as Countess of Chatham in July 1783, “dressed in white sattin, richly trimmed with silver fringe &c. Her head-dress was elegant, and she looked very beautiful”.[26]

Jacqui Reiter has a PhD in 18th century British political history. She is currently working on her first novel, which deals with the second Earl of Chatham's troubled relationship with his brother William Pitt the Younger. She blogs at http://alwayswantedtobeareiter.wordpress.com/

References

[1] Andrew Tink, Lord Sydney: the life and times of Tommy Townshend (Melbourne, 2011), p. 152

[2] Lord Sydney to Lady Chatham, 13 July 1783, PRO 30/8/60 f 207

[3] Marriage settlement of the 2nd Earl of Chatham and Mary Elizabeth Townshend, 5 July 1783, Bromley Archives 1080/3/1/1/26

[4] Georgiana Townshend to the Dowager Countess of Chatham, 20 April 1784, National Archives PRO 30/8/64 f 167

[5] Rev. Edward Wilson to the Dowager Countess of Chatham, June 1785, PRO 30/8/67 f 110

[6] I am grateful to Lucinda Brant for providing me with information on Miles Partington. He detailed his theory on electrical therapy in a 1779 treatise for the Royal Society entitled “A cure of a muscular contraction by electricity” (London, 1779). For Mary's treatment in the 1780s, see Georgiana Townshend to the Dowager Countess of Chatham, undated, National Archives PRO 30/8/64 f 170; for 1796, see Lord Bathurst to Earl Camden, 27 February 1796, Kent RO CKS-U840/C95/2. For Mary's lameness see the Dowager Countess of Chatham to William Pitt, 14 October 1795, National Archives PRO 30/8/10 f 31

[7] This is clear from Rev. Edward Wilson's congratulations to the Dowager Countess of Chatham: he notes that he received notice of Mary's pregnancy “from the very highest Authority”, presumably either Mary herself, or Lord Chatham. Wilson to the Dowager Countess of Chatham, 5 November 1786, National Archives PRO 30/8/67 f 134

[8] Georgiana Townshend to the Dowager Countess of Chatham, undated, PRO 30/8/64 f 187

[9] London Chronicle, 28 March 1789

[10] Georgiana Townshend to Catherine Stapleton, February 1793, in Memoirs and Correspondence of Field-Marshal Viscount Combermere... vol 2 (London, 1866), 419-21

[11] For the Glorious First of June see Peter Jupp (ed), The Letter Journal of George Canning, 1793-5 (London, 1991), p. 121; for Mary following Chatham throughout his military career see the Prince of Wales to Lord Chatham, 2 September 1799, National Archives PRO 30/70/4 f 219 and William Pitt to Mary Chatham, 13 September 1798, National Archives PRO 30/8/101 f 141. For the military review see Princess Elizabeth to Mary Chatham, 22 June 1800, National Archives PRO 30/70/6/13/52, and the Whitehall Evening Post for 24 June 1800

[12] Times, 5 June 1793; Times, 19 January 1791; Lady's Magazine, vol XXXIII (1802), 40

[13] Mary Chatham to Catherine Stapleton, undated but after 1792, in Memoirs and Correspondence of Field-Marshal Viscount Combermere... vol 2 (London, 1866), 426

[14] Manuscript poem entitled “The Countess of Chatham”, Bromley Archives 1080/3/6/6/10

[15] Mary Chatham to William Pitt, undated but summer 1800, British Library Add MSS 89036/1/17 f 44

[16] “his Sister-in-Law, Lady Chatham, could not bear him”: in The Jerningham Letters (1780-1843)... vol 1 (London, 1896), 322

[17] George Tomline, Bishop of Lincoln, to Elizabeth Tomline, 31 January 1806, Ipswich RO HA 119/T99/26

[18] Lord Chatham to the Earl of Dartmouth, 6 February 1806, in HMC Manuscripts of the Earl of Dartmouth, p. 290

[19] Anonymous [possibly Mary's sister Georgiana Townshend] to Dr Henry Vaughan, 14 April 180[7], Leicestershire RO Halford MSS DG 24/819/1 and DG 24/819/2; Manuscripts of J.B. Fortescue preserved at Dropmore... IX (London, 1915), 171, Thomas Grenville to Lord Grenville, 9 January 1808

[20] Mary's 1818-20 illness is documented in some detail in the correspondence between Lord Chatham and George Tomline at Ipswich Record Office, HA 119/562/688. Mary's mental state in September is covered rather luridly in a long letter from Mrs Tomline to Sir Henry Halford, undated but early September 1819, Ipswich RO HA 119/562/716

[21] Sir Henry Halford to Elizabeth Tomline, 10 September 1819, Ipswich RO HA 119/562/117 for the straitjacketing; and Lord Chatham to George Tomline, 22 September 1819, HA 119/562/688 for Chatham's refusal

[22] The Times, 30 April 1821

[23] Morning Post, 12 May 1821

[24] Morning Post, 23 May 1821. For the obituaries see the Morning Post itself, on 25 May 1821; also the Gentleman's Magazine vol 91 part 1, 565; European Magazine and London Review vols 79-80, 561; The Examiner 1821, 335

[25] Gentleman's Magazine vol 91 part 1, 565

[26] Morning Chronicle, 1 August 1783

Written content of this post copyright © Jacqui Reiter, 2014.

.jpg)

![[Image 6: 38 Hill Street, now the Naval Club, where Mary died: photograph by Stephenie Woolterton]](https://1.bp.blogspot.com/-rmRS6eT7Jh4/U3Y-33sLQGI/AAAAAAAAC0Q/r7oaFVJCrYI/s1600/unnamed.jpg)